The history of modern social networks in Japan goes back to 2004, when the online profile-based social networking site Mixi was established. It quickly gained traction to become the leading social network destination in Japan, with more than 17 million monthly users.

However, Mixi is not as popular as it used to be and there are now more Twitter users than Mixi users. As early as December 2011, an online research company claimed that Facebook had a higher number of monthly unique visitors than did Mixi.

Nowadays, all of these major services seem to have been surpassed by LINE, a group chatting application that can be considered a social media platform (it has a newsfeed, timeline, and many-to-many communication functions). Recently, LINE reported that it registered about 47 million users in Japan, almost equivalent to Japanese Facebook and Twitter users combined.

Past studies indicated that Japanese users prefer local social networks that reflect Japanese social values. Japanese online social networks, in general, consist of smaller and tightly knit social circles and promote anonymity, long-term commitment, and indirect communication, which are all part of Japanese culture.

Mixi users, for example, are usually considered introspective and conservative when presenting themselves on the network. These findings imply that Japanese social media behavior is quite different when compared with Western users.

Nevertheless, some people may argue that online social network usage in Japan has been changing with the rising popularity of real name–based social networking platforms and the impact of globalization, which is accelerated by social media. Yet our recent studies provided empirical evidence that Japanese social networking behavior still differs from that of Western countries.

We found that more than 80% of Japanese social media users are reluctant to use their real name and real pictures in social media and the ratio of people who prefer anonymity today is not significantly different from the past. In another study in which we compared the tweets of American and Japanese college students, we observed that the content of social-media messages in Japan also tends to be quite different, as Japanese college students usually tweet about TV dramas and rarely ask for help while American college students tend to post messages related to sports and ask many questions publicly.

By the same token, while conducting a qualitative study that compared Japanese and American students’ Facebook use, we were surprised to find that Japanese students responded to every single comment on Facebook, preferred smartphones over computers for social networking, and felt more positive about social media use in the classroom than did American subjects. Similarly, when it comes to commercial social media usage, Japanese companies tweet less frequently than their foreign counterparts, use hashtags less often, and usually do not allow their fans to post on their brands’ Facebook walls. All these findings confirm that Japanese social media use is still quite different from that of Westerners.

Ruth Benedict claimed that Westerners have a hard time understanding Japanese culture because Japan is a country of contrasts. This applies to social media as well. For instance, Japan constantly scores at the bottom of global social media engagement indexes, yet Japan has the highest blog readership in the world.

Japanese tend to be very other-oriented, but Japan is the only country where Twitter, which promotes self-broadcasting, is more popular than Facebook or Mixi. Japan is known to be a tech-friendly country, but it consistently lagged behind Western countries in computer adoption.

Of course, many of these can also be explained by Japan’s demographics: Japan has one of the most aged populations in the world (25% of the population is 65 or older).CIA World Fact Book/Japan Regardless, it seems Japan has highly unique social media use patterns.

Japanese Social Media

In March 2012, we conducted a large-scale study by using the online panel of Kansai Electric Power Company. With the participation of 1,000 online Japanese users from different age groups, our study generated quite useful insights about social media use in Japan.

Very similar to what the Pew Research Center found, we observed that about half (54%) of the Japanese Internet users did not have any social media account. When asked a single-choice question about which social media site they preferred, 14% indicated Twitter, followed by 13% for Facebook, and 12% for Mixi. Around the same time, a Japanese market research company asked more than 10,000 online users which social media platforms they signed up for; it also found that Twitter was the most popular platform in Japan, with 29% of Internet users mentioning that they had a Twitter account.

In the nationwide study we conducted, we wanted to know what distinguished social media users from non-users and why people use social media. Our initial analysis showed that females and young Internet users were more likely to be users. When it comes to personality, there was only one trait that differentiated users from nonusers: extroversion. Obviously Japanese people who were social and extroverted were more likely to be involved with social media.

Although extroverts used social media more, we were very surprised to discover a unique top activity in social media, as it was not related to a social activity per se. In order to find out what people did in social media, we gave respondents twenty-four online activities and asked them to indicate whether they performed each activity on their preferred social media platform (Mixi, Twitter, GREE, Facebook, Google+, etc.).

We observed that neither social bonding nor information gathering activities topped the list. It was killing time, followed by enjoyment: both individual and escapism-related activities.

We believe long train commutes in Japan and the traditional manga culture that promotes escape from reality play a role in this behavioral outcome. On the other hand, finding a partner, joining discussions, and using social media for work or job hunting were the least common activities performed by Japanese social media users.

As part of a modest and reserved society, the Japanese may abstain from joining public discussions on the Internet. One should also note that career-oriented platforms like LinkedIn, human resources applications, and dating networks may have a hard time penetrating the market in Japan, as Japanese people use social media mostly for different purposes.

Facebook in Japan

One particular aspect of Japanese Internet users is their low engagement rates in content creation. In the study we conducted in March 2012, we asked respondents to indicate what they have done on Facebook in the past two months. As one can guess, a small fraction of users mentioned updating their status in social media. Comparing these values with American users (in the left column), one can see that American users are more active:

Note: N=229 Japanese Facebook users, nationwide sample (Acar & Fukui, 2012);

N=269 American Facebook users, nationwide sample (PEW, 2012)

Alternatively, the results indicate that Japanese users can be quite active when it comes to participating in promotional campaigns, as the percentage who joined a commercial campaign on Facebook is larger than those who updated their status. Supporting this finding, a market research company found that more than half of Japanese college students wanted to follow their favorite brands on multiple platforms (e.g., following Coke on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Pinterest versus just following it on a single platform), while this ratio was less than one-third among the American sample.

Furthermore, when we compared German, American, and Japanese Facebook fans’ reactions to brands’ posts, we found Japanese were ten times more likely to Like a brand post on Facebook but at the same time about ten times less likely to share and five times less likely to comment on those posts compared to American consumers. In other words, if Coke had an equal number of fans in Japan and the United States (let’s say one million), when it posts a message, it is likely to get about 16,000 Likes in Japan versus 1,600 Likes in the United States.

However, total comments and shares may be the same in each country because American users are more likely to share and comment on branded posts. We think because Japanese are very considerate of others, sharing a message with friends who may not be fans of another brand may be seen as very rude in Japan. Additionally, publicly commenting on brands’ posts may make Japanese feel different from others, and in a harmony-based society people may not want to publicize their brand choices. See the following table.

As behavior on Facebook may strongly depend on demographic characteristics, we also compared the same gender and the same occupation (student) subjects from Japan and the United States. The American sample consisted of 229 female members of a college-student online panel operated by a private market research company, whereas the Japanese sample included 31 female college students from a Japanese public university.

The results were very similar to the previous findings, showing far more active American subjects as indicated by the graph below. Particularly, the percentages of students who updated their status and posted a photo showing their face were far lower in the Japanese sample.

We also asked the students their friend count on Facebook and the results showed that U.S. female students had on average 475 friends, much higher than the average friend count of 148 in Japan. Although the difference in the friend count was also statistically significant, because there was too much variation in the data we thought comparing only the average number of friends may not be a good idea.

Author’s Note: For this study we used the online panel of a private market research company located in New York City. This company has more than 200,000 panel members in North America who get points for performing several online activities including taking online surveys. The college student panel is demographically representative, as there were students from 46 out of 52 states, about 58% of whom aged between 18 and 24. The distribution of 18–24 year olds is basically the same as the data provided by the U.S. Census bureau four years ago (58%). Additionally, a recent PEW report indicated that 92% of 18–29-year-olds had a smartphone, a ratio similar to what we observed in our dataset (90%). The data collection took place between September 6 and 9, 2013, and the respondents earned badges for taking the online survey.

(Sources: http://www.pewInternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2013/PIP_Smartphone _adoption_2013.pdf, http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables /12s0281.xls)

Another interesting finding that emerged from this cross-cultural comparison was the difference in profile-picture preferences. As Japanese are known to value anonymity and use avatars rather than real pictures, they seemingly maintain this culture on Facebook as well.

While most Americans choose to have a “solo shot” profile picture, most Japanese users either had a “group shot” photo or simply a picture of something else. Although this is an improvement compared to the 20% real photo profiles on Mixi1 three years ago, Japanese users still are highly different from American users when it comes to profile-picture choices.

On the other hand, we were surprised to see that more than one-third of Americans posted a “group shot” as a profile photo, as Facebook literally means “face book”: the traditional high-school yearbook that shows each student’s solo shot. However, we suspect that females are more group-oriented and emotionally attached to their peers, and these ratios may differ for American males.

Speaking of group orientation, selfishness, and social attachment, we measured “fear of missing out” and narcissism among both American and Japanese subjects. Fear of missing out means concern about not joining social events, as well as the inclination to share social activities with friends.

We found that the two nations did not differ on this dimension; however, Americans scored significantly higher than did the Japanese on the narcissism scale (questions like “People tell me I am attractive,” “I believe I can influence people,” etc.). At the same time, while narcissistic tendencies predicted whether American subjects posted pictures on Facebook or not, it had no impact on Japanese subjects. In other words, a Japanese person’s online posting is not that much influenced by whether he or she has narcissistic tendencies.

Lastly, we wanted to test whether the findings we obtained in our focus interviews with Japanese and American subjects could be replicated in large-scale data. Particularly, we wanted to know if American subjects felt more comfortable sharing private information, using Facebook for educational purposes, and adding strangers to their networks.

We generated many different scenarios that involved Facebook use and asked both American and Japanese subjects if they would have felt comfortable taking the action indicated in each scenario. The findings confirmed most of our expectations as shown in the following table:

As can be seen in the table, American subjects felt much more comfortable sharing information on Facebook than did Japanese students. The groups scored the same on the question asking about whether they would friend someone on Facebook after chatting with that person at a café for the first time.

The biggest differences that caught our attention were Japanese participants’ reluctance to share a photo that shows either their partner or their family. Although Japanese are known to be very family-oriented people, obviously sharing family information publicly goes against Japanese values.

Furthermore, just as we found in our focus-group study, it appeared that Japanese subjects were more interested in friending their professors than were American students. This is an interesting finding because in Japan usually students use keigo (honorific language) when talking to their professors and want to maintain distance between themselves and those whom they think are erai (people with social power).

The fact that they want to be Facebook friends with their professors, but do not want to be friends with their parents or share a picture of a romantic partner, implies that Japanese people see Facebook as an official platform that can be used for information gathering rather than emotional bonding.

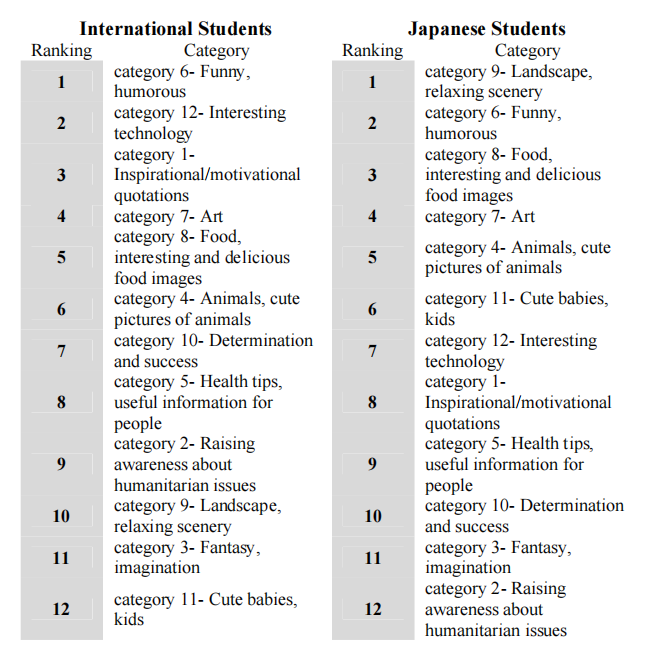

In a similar but separate study we asked Japanese and international exchange students what kind of content they would Like on Facebook. Since we did not have enough American and Western subjects, this time we mixed the responses of all international participants who came to Japan as exchange students (the data was collected in 3 different universities in Japan where the principal investigator taught part-time during the month of May, 2013). Different than the study mentioned above, we did not focus on any particular gender and about two thirds of the respondents were from different parts of Asia, not from Western countries.

The question asked:

Please carefully look at the examples above for each category. Based on your past experience on Facebook, please indicate (on a scale of 1 to 7) whether you would Like these kinds of posts on Facebook or not?

We did not observe a large number of differences between Japanese and international students except for the “landscape” and “cute babies & kids” categories. The fact that everything in the previous study was dramatically different and this time there were not many differences, made us conclude that Asians may not differ that much in terms of content sharing on Facebook as most of the international students were Asian.

However, we think it begs an explanation why Japanese people are more likely to share the images of landscapes and cute children. Some people may speculate that females may be more interested in the pictures of babies and if the Japanese sample had a higher ratio of female subjects, this may have biased the data. However, when we compared only female students from both samples, the difference was still significant. Japan’s zen culture that emphasizes the harmony between man and nature and the concept of “kawaii” (all little things are loveable whether they are cute or not) may have driven these differences.

Disclaimer: The author does not own these images.

The images were gathered over the internet for research purposes.

Additionally we also looked at the rankings of each category. Although the differences were not statistically significant, the rankings also indicated that Japanese college students are less interested in “quotatiations,” “interesting technology” and “raising awareness about humanitarian issues” compared to their Asian counterparts. Interestingly, the “fantasy/imagination” category was not rated as highly by Japanese respondents even though escapism promoted by the common “manga” subculture in Japan may suggest otherwise.

Facebook and Business in Japan

We also asked both American and Japanese subjects about their attitudes toward social media. Both Japanese and Americans had positive attitudes towards social media as more than two-thirds of the subjects disagreed with the statements “Social media is bad for our society” and “Social media has more demerits than merits.”

Both American participants and Japanese participants thought social media was good for society (see appendix). Since Japan is a risk-avoidant society and since recently there has been much discussion in the Japanese media about privacy issues caused by social media, we thought that Japanese would have more negative views of social media than did Americans, but the findings showed that Japanese still think positively about social media.

People may wonder if the content people post on Facebook brand walls differs across the Pacific. One of the students from my social media seminar looked at the last five messages posted on thirty Japanese and American brands’ Facebook walls.

After compiling a total of 191 messages from comparable brands (exactly the same brands or brands from the same industries, as some Japanese brands did now allow their fans to post on their walls) in Japan and the United States, he concluded that what people tell brands is pretty much the same in both countries except for two striking differences: negative emotions and visual information. While only a small fraction of Japanese consumers complained about or criticized brands on a Facebook wall, about a quarter of Americans posted a negative message publicly on Facebook.

Additionally, Japanese users posted more visual information (photographs, emoticons, etc.) on brands’ walls, perhaps a reflection of high-context Japanese culture that shows preference for visually rather than verbally expressed emotions. Another surprising aspect of this finding is the similar ratio of positive comments in both countries, as we expect Americans to post more positive statements.

A study conducted in the 1980s showed that Americans compliment each other five times more frequently than do the Japanese, and Americans tend to be more elaborate when complimenting others. This interpersonal communication pattern was not reflected on online brand-consumer conversations.

After these interesting findings we decided to deeply analyze the data from the cross-cultural study where we compared Japanese, German, and American brands’ posts and consumers’ reactions to them. The methodology was very simple: categorizing the last ten Facebook messages of the same brands or similar brands (in case the same brands are not available) in Japan, Germany, and the United States.

In September 2012, two bilingual coders, one from Japan and one from Germany, classified 350 posts from Japan, 350 from Germany, and 350 from the United States. In each country, we selected thirty-five brands that represented seven different categories (Food & Beverage, Automotive, Electronics, Clothing, Health & Beauty, Travel, and Finance).

As can be seen in the graph below, Japanese companies use the word “you” less often and recommend that users Like, share, or comment less frequently. At the same time, Japanese brands post more images and more links.

All these findings reflect the high-context and indirect style of Japanese communication, as Japanese companies do not want to be seen as aggressive and pushy. As part of the soft-selling method common in Japan, brands provide visually appealing information or links to their sites but do not pressure Facebook users to take action.

Source: Takamura (2013)

Source (Acar & Rauschnabel, 2013)

As predicted, we observed that Japanese posts had significantly fewer words than did American and German posts. Since Japan is a high-context country that puts more emphasis on visual messages we thought this finding was normal. However, we should also remember that counting Japanese characters that include some kanji may not be comparable with counting Roman characters because one kanji may represent a word or a whole phrase.

Additionally, in the Japanese language, subject pronouns are usually omitted. On the other hand, it is worth exploring why German posts had longer text than did American posts, as both countries have relatively similar communication styles.

In a separate study our team also investigated the top hundred Japanese brands and the US brands’ Facebook and Twitter activities in January 2012. Our initial analysis has shown that fewer Japanese brands are active both on Twitter and Facebook when compared with the top US brands. We also observed that Japanese brands, in general,

- ask fewer questions,

- post less frequently,

- do not address their fans directly,

- do not initiate conversations,

- reveal less info, and

- do not allow their fans to post on their walls.

The top hundred American brands investigated in this study seemed to be far more active and assertive compared to their Japanese counterparts. We concluded that the low dialogic communication between brands and consumers in Japan can be explained by three cultural factors:

- Japan is a high power-distance country, meaning there may be a power imbalance between consumers and corporations, with power skewing toward the latter. That is why “neither consumers nor large and well-respected corporations might feel so comfortable with publicly exchanging messages that would be read by everyone.”

- “Japan is a culture of reservation and harmony; some marketing executives in Japan might just think it is very intrusive to send out many personal messages or ask questions on Twitter or Facebook.”

- Japan is a risk-avoidant country and social media involves many risks. Some managers may think it better to stay away from or use social media passively rather than actively using it every day and engaging with customers.

Twitter in Japan

As mentioned above, Twitter is the most popular social media platform (excluding peer-to-peer group messaging app LINE) in Japan and Japan is the only country where Twitter is more popular than Facebook. What is more, Japan is the third-largest country on Twitter, with more than 35 million users.

Japanese is the second most popular language on Twitter and in the year 2012 the top-two most tweeted moments in the world were related with Japan (Castle in the Sky Japanese TV program with 25,088 tweets per second, and the Japanese New Year, with 16,197 tweets per second). So the question is: Why is Twitter so popular in Japan?

It is not so difficult to answer this question and some potential explanations follow:

- Even before Twitter was introduced, the Japanese online community had been interested in blogging. A survey from 2006 indicated that 74% of average Internet users in Japan read blogs.33 These ratios were far higher than any other developed country back then, which shows how interested Japanese are in blogs. Since Twitter is a form of micro-blogging, it makes sense that it is successful in Japan.

- Japan is a culture of harmony. People avoid publicly criticizing; however, suppressing negative feelings and not venting them may cause stress. Hence, there is a platform called 2Channel where people criticize others, spread rumors, and freely express themselves by just using nicknames. Since Twitter is a nickname-based platform, it is suitable for many who want to criticize things without revealing their true identity. Additionally, we should not forget that the majority of the Japanese still feel uncomfortable using their actual names and pictures in social media.

- An early study that compared Mixi and Facebook found that 80% of Japanese users write diaries on Mixi, while almost no one writes a diary on Facebook. Since Tweeting what you are up to is like writing a short diary, we can speculate that this is one of the reasons why Japanese love Twitter.

- Japan is geographically small; it has only one time zone (in the United States there are four) and only six major network channels. This makes it easier for Twitter users to consume the TV content together. In this case, both TV and Twitter serve as a glue that helps the Japanese preserve cultural values and experience a sense of solidarity.

One may argue, “But what about the earthquake?” Although the earthquake caused an immediate spike in both Twitter and Ustream usage, in the long run it had almost no impact on the popularity of Twitter, as can be clearly seen in the graph below.

The graph, which shows the number of Google searches for each platform in Japan, generated by Google Trends TM, also makes very clear that Facebook’s meteoric rise cannot be directly tied to the earthquake either. Even though the immediate changes can be seen on Twitter and Ustream users, obviously the number of Facebook users did not increase for the following four to five weeks.

Therefore, neither Facebook’s nor Twitter’s large Japanese user base can be tied to the earthquake. Based on the decrease in the popularity of both Ustream and Twitter in the long run, we can also speculate that large-scale events like disasters or social protests that cause sudden increases in the use of certain platforms may not have long-lasting effects.

Two unique characteristics of Japanese Twitter users that may distinguish them form Western users are perhaps the number of accounts followed and percentage of protected accounts. When we conducted the online survey, we asked the subjects how many Twitter accounts they follow and how many followers they have in total. We also asked the same question to our Japanese students (N=71).

The follower-to-followee ratio was almost the same in both countries (0.91 versus 0.89), indicating that both in Japan and the United States, social media users, in general, follow more people more than the number of their own followers. However, it seemed Americans on average follow about 141 accounts and that number is only 105 among the Japanese.

Since the difference was statistically significant, we concluded that Japanese follow fewer people on Twitter than do Americans. We think this may have to do with a higher desire for popularity in the US as in order to get more followers, people follow more people.

Additionally, this finding is in line with past research that concluded that Chinese users don’t care much about being popular online (e.g. they don’t see social media as a platform for a popularity contest) compared to American social media users. There may also be another reason for this phenomenon, which is the prevalence of protected accounts in Japan.

We also asked our subjects whether their Twitter account is “protected,” meaning their tweets are not public and can only be seen by a select number of people. To our great surprise, about 25% of Japanese respondents said that they had a secure Twitter account and their tweets cannot be publicly seen.

This ratio is predicted to be less than 7% throughout the world.37 The fact that many Japanese users do not make their tweets public indicates that they limit their messages to friends and family just like exchanging messages in traditional social networking platforms. In other words, for about a quarter of Japanese Twitter users, Twitter may be acting like a relationship-based social network rather than an information or interest network.

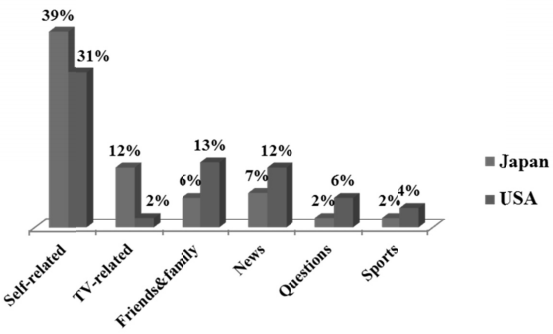

We can’t understand Japanese Twitter use completely without crossculturally comparing the Twitter content to another country. A student of mine classified the ten last tweets of one hundred Japanese and one hundred American students during the first week of December, 2011 (a total of two thousand tweets).

The results showed that the Japanese posted more self-related messages and things related with TV. On the other hand, American tweets had significantly more references to news, sports, politics, and family.

We concluded that Japanese post more self-related messages because mentioning others might be intrusive. For instance, if I mention my friend in my message, he or she may feel compelled to reply or deeply wonder if the message meant something else (remember Japanese communication style tends to be indirect).

Additionally, as indicated by past studies, the perception of intimacy in Japan and the United States are likely to be different. Japanese people love and respect their families but that does not necessarily mean they exchange verbal messages in social media.

On a further note, we think Japanese TV-related tweets were far higher than the US ones perhaps because of the impact of TV shows and dramas on Japanese social life and Japan’s single time zone (all Japanese can watch the same drama at the same time but in America people on the East and West coasts watch the same dramas at different times). We also found that most trending topics on Japanese Twitter were related to TV. This means, the popularity of social media, particularly Twitter, may actually strengthen TV’s popularity in Japan, as it seems Twitter acts as commercial tool to promote TV dramas.

Politics and Government

We explored how politicians and local governments in Japan have been using social media and if there were cross-cultural differences in the use of these mediums. Because of small sample sizes and the lack of multiple coders, statistical tests were not run but the initial findings were eye-opening.

In both of the studies my students coded the last ten messages by the most popular ten accounts in Japan and the United States (the ten most popular politicians, and the ten most popular states and prefectures) during the month of January in 2013. Although Japanese local governments’ postings reflected Japanese values, Japanese politicians’ tweeting patterns seemed a little bit unusual.

For instance, Japanese are known to be less assertive and aggressive than Americans, but there was more criticism in the tweets of Japanese politicians compared to those posted by American politicians. Furthermore, Japanese politicians’ messages were also more direct and action-oriented than the tweets of American politicians. The findings and the detailed graphs are available at http://www.slideshare.net/adamacar.

Main differences between Japanese and American politicians’ Twitter use:

- Japanese values are not necessarily reflected in Japanese politicians’ tweets, or, Japanese politicians who actively use Twitter may not be mainstream politicians.

- Although Japanese people tend to criticize others less and state their own opinions less compared to Americans, our results indicate that, on Twitter, Japanese politicians are more outspoken than their American counterparts.

- Self-promotion and promotion of another person or group for doing a good job was much more common in the United States. This may be related with the group-oriented nature of Japanese culture where groups but not individuals are the main focus.

Main differences between Japanese and American local governments’ Twitter use:

- American local governments mostly tweet about local news, while Japanese prefectures tend to focus on informing people about local events and activities.

- American local governments ask many questions but Japanese prefectures do not.

- American local governments tend to thank followers and show appreciation (verbally) while Japanese prefectures do not.

- Reference to blogs is almost nonexistent in the United States.

- Tips and useful information are almost nonexistent in Japan.

Based on all the studies cited above we conclude that:

- Japanese users are uncomfortable sharing their real names and profile pictures online,

- Japanese people in general don’t feel a need to share anything personal about themselves in social media

- Japanese don’t want to be seen different from others

- Japanese people think sharing online content may disturb others,

- Japanese people feel uncomfortable asking questions in social media and interacting with strangers online,

- Japanese people use social media mostly for killing time or escaping the stress of daily life and

- Japanese people care a lot about their own privacy and others’ privacy.

Emerging Social Media Platform: LINE

LINE is a popular group-messaging platform owned by a Korean company based in Tokyo, Japan. Currently LINE has more than 230 million active users in more than two hundred countries.

It is the biggest social media platform in Japan, with more than 47 million registered users; it is reportedly the fastest-growing communication medium in history, as it reached the 100 million user mark within nineteen months. Twitter and Facebook, in contrast, took forty-nine and fifty-four months respectively to pass this milestone. The company is also very profitable; in the first quarter of 2013 it reported revenues of $58 million, which can be used to expand the company in countries outside Japan.39

People can do many things with this application, including:

- calling people for free,

- chatting,

- group-chatting,

- timeline updating,

- getting coupons,

- playing games, and

- collecting digital stamps.

Since it has a timeline and many-to-many messaging options, it can be considered a social networking platform and it seems to be the most popular social media tool, especially among college students (see the graph below). Although it is speculated that LINE became popular in Japan because phone lines went down after the earthquake, it is likely that this is not the main reason.

Our focus group with high school students in early 2012 showed that LINE first picked up among high school students in major cities that were not affected by the earthquake. Additionally, before LINE started in Japan, the United States had WhatsApp, China had WeChat, Korea had Kakao Talk, all of which are extremely similar to LINE. In Japan, however, there was no local application that allowed free message exchanges and smooth free calls.

In February 2013, we asked college students how they used social media platforms and about 58% of them indicated using LINE almost every day, more frequently than Facebook, Twitter, and Mixi. LINE use was so popular that students even indicated LINE would be their first-choice social media tool if a disaster were to strike.

We also asked participants how many brands they follow on LINE and on Facebook. It was clear that LINE followers were more likely to follow a brand compared with Facebook users.

About 60% of LINE users were following at least one brand, whereas only 30% of Facebook users reported following a brand. LINE also seems to be very popular among Japanese brands, despite the fact that it charges each company about $7,000 just to have a LINE account for only six months.

Our content analysis of the last ten LINE messages of six major brands (au, Sukiya, Tsutaya, Shiseido, Lawson, and Coca-Cola) from six different industries showed that what brands do on LINE is similar to what they do on Twitter (giving away coupons, providing campaign information, and presenting the latest news about products and services). However, it was found that they send messages with many emoticons (smiles, heart marks, etc.) that may seem very friendly and personal, the messages are longer, and these messages are rarely sent (e.g., a few times a month).

One important element that distinguishes LINE from all other platforms in terms of brand communications is that it allows brands to create digital icons/stickers called stamps and distribute them to their fans. One may wonder why people would want to download these digital icons and then share them with their friends; the trick is these stamps can be useful to express emotions (basically stamps replace traditional emoticons).

Instead of sending the message Merry Christmas and adding a smiley face or a tiny holiday-related image, users may send a cute Coca-Cola–themed stamp that their friends perhaps don’t have. Consumers sometimes can receive these stamps right after following a brand on LINE, or they may need to perform an activity (join a campaign or buy the product) in order to get a code that can be used to download the stamp. Once downloaded, users can see the stamp in their emoticon library to use in conversations whenever they want.

These stamps or digital stickers have several implications. First of all, Japan is a high-context culture that puts special emphasis on nonverbal expressions of emotions, and obviously LINE’s user base skyrocketed in a short time because LINE provided rich opportunities to express emotions with its stamps’ messaging platforms.

As a matter of fact, our data shows that 87% of LINE users downloaded additional stickers (even though the app comes with at least thirty free stickers different from those on any other platform), 62% used branded stickers (stamps), and 25% purchased more stickers sold by LINE. Secondly, using LINE stamps issued by brands is very valuable both for brands and consumers.

It is a subtle soft-selling technique that makes consumers share brands’ logos for free. At the same time, for consumers, it is an unobtrusive and rewarding way for them to share their interest in a particular brand, to show that they are unique (since not everyone has the same branded stickers, most of the time it is a unique thing to include a branded sticker in a conversation), and to communicate their personality as brands we use reflect our image.

References

- Barker, V., & Ota, H. (2011). Mixi diary versus Facebook photos: Social networking site use among Japanese and Caucasian American females. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 40(1), 39– 63.

- Thomson, R., & Ito, N. (2012). The effect of relational mobility on SNS user behavior: A study of Japanese dual–users of Mixi and Facebook. The Journal of International Media, Communication and Tourism Studies, 14(1), 3–22.

- comScore (Dec. 21, 2011) . It’s a Social World: Social Networking Leads as Top Online Activity Globally, Accounting for 1 in Every 5 Online Minutes. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.comScore.com/Insights/Press_Releases/2011/12/Social_Ne tworking_Leads_as_Top_Online_Activity_Globally

- Osawa, J. (2013). Messaging App Line Expands Outside of Japan. The Wall Street Journal Digits. Retrieved Dec 26, 2013, from http://blogs.wsj.com/digits/2013/08/27/messaging-app-line-expands-outside-of-japan/

- Fogg, B. J., & Iizawa, D. (2008). Online persuasionp in Facebook and Mixi: A cross–cultural comparisonccc. H. Oinas–Kukkonen, P. Hasle, M. Harjumaa, K. Segerståhl, & P. Øhrstrøm (Ed.), Persuasive Technology (Vol. 5033, p 35–46). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg

- Acar, A., Nishimuta, A., Takamuea, D., Sakamoto, K., & Muraki, Y. (2012, February). Qualitative Analysis Of Facebook Quitters In Japan. In Proceedings of the Eight International Conference on eLearning for Knowledge-based Society.

- Thomson, R., & Ito, N. (2012). The effect of relational mobility on SNS user behavior: A study of Japanese dual–users of Mixi and Facebook. The Journal of International Media, Communication and Tourism Studies, 14(1), 3–22.

- Lin, C. A. (2012). International advertising theory and methodology in the digital information age. In Handbook of Research on International Advertising (pp. 279-302).

- Takahashi, T. (2010). MySpace or Mixi? Japanese engagement with SNS (social networking sites) in the global age. New media & society, 12(3), 453-475.

- Hays, J. (n.d.). Japanese social life, friendship, singing, teasing, and smiling. Web Log Post Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://factsanddetails.com/japan/cat18/sub115/item613.html

- Acar, A. & Fukui, M. (2012) . The social media landscape of Japan. Paper Presented at the 2012 IBSM International Conference on Business and Management, Phuket, Thailand.

- Acar, A., & Deguchi, A. (2013). Culture and social media usage: Analysis of Japanese Twitter Users. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 4(1), 21-32.

- Acar, A. Ohniwa, Mio, Ando, Saki & Hatada, Saki (2013). The Differences between Japanese and Americans: A qualitative Assessment of Facebook Usage. Paper Presented at the 2013 IBEA Conference, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Acar, A., Takamura, D., Sakamoto, K., & Nishimuta, A. (2013). Culture and brand communications in social media: an exploratory analysis of Japanese and US brands. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 9(1), 140-151.

- Benedict, R. (1967). The chrysanthemum and the sword: Patterns of Japanese culture. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: New York, NY.

- IPSOS OTX News & Polls (Aug. 13, 2013). 71% of Global Internet Users “Share” Social Media Content Monthly: Pics (43%) plus Opinions, Status Updates and Links to Articles each Top Out at 26%. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.ipsos-na.com/news-polls/pressrelease.aspx?id=6216 Culture

- comScore (Aug 24, 2011) Top global markets for blogs. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.comScoredatamine.com/2011/08/top-global-markets-for-blogs/

- Yarow, J. (2012). There’s only one place in the world where Twitter is bigger than Facebook. Business Insider. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.businessinsider.com/theres-only-one-place-in-the-world-where-twitter-is-bigger-than-facebook-2012-1

- De Mooij, M. (2010). Consumer behavior and culture: Consequences for global marketing and advertising. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2013). TheWorld Factbook: Japan. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/ geos/ja.html

- Pew Research Center (2012). Social networking popular across globe. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.pewglobal.org/!les/2012/12/Pew-Global-Attitudes-Project-Technology-Report-FINAL-December-12-2012.pdf.

- Cross-marketing Ltd. and Tribal Media House Ltd. (2012). 2012 White Paper on Social Media. Tokyo: Shoeisya, Ltd

- Acar, A., Rauschnabel, P., Lin, C & Makoto, F. (2012). The relationship between personality and social media preferences. Proceedings of the 45th Annual Conference of Japan Association of Consumer Studies.

- Hampton, K. N., Goulet, L. S., Marlow, C., & Rainie, L. (2012). Why most Facebook users get more than they give. Pew Internet & American Life Project,3.

- News2u News Release. Differences between University Students in Japan and the United States in the Use of Social Media. Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.news2u.com/news/20130304.html

- Acar, A & Rauschnabel, P. I can’t share this: Cross-cultural analysis of consumer reactions to Facebook posts in Japan, Germany and the US. In Proceedings of the 47th Annual Conference of Japan Association of Conusmer Studies, Tokyo, Japan (pp. 77-80).

- Takamura, D. (2013). What Do People Tell Brands on Facebook? A Comparison of Japanese and American Facebook Users. Unpublished graduation Thesis. Kobe CIty University of Foreign Studies, Tarumi, JP.

- Barnlund, D. C., & Araki, S. (1985). Intercultural Encounters The Management of Compliments by Japanese and Americans. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 16(1), 9-26.

- Ahramonline (n.d.). Twitter clocks half-billion users:Monitor. Published Online Retreived http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/2/9/49107/World/Internation al/Twitter-clocks-halfbillion-users-monitor.aspx

- Leetaru, K., Wang, S., Cao, G., Padmanabhan, A., & Shook, E. (2013). Mapping the global Twitter heartbeat: The geography of Twitter. First Monday,18(5).

- Di Costanzo, L. (Jul 18, 2012). Top 20 most tweeted moments: Twitter rises above the sky. Web Log Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://blog.seevibes.com/social-media/top-20-most-tweeted-moments-twitter-rises-above-the-sky/

- Rivera, M. (March 22, 2007). Japanese read blogs more than you. Web Log Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.blogherald.com/2007/03/22/japanese-read-blogs-morethan-you/

- Youssef, S. (2009). Geeks and creeps in no name land: triangulating anonymity, 2channel and Densha Otoko (Doctoral book, University of British Columbia).

- Google Trends. Retrieved Dec 26, 2013, from http://www.google.com/trends/explore#q=facebook%2C%20twitter%2C%20UStream&geo=JP&date=1%2F2011%2012m&cmpt=q

- Jackson, L. A., & Wang, J. L. (2013). Cultural differences in social networking site use: A comparative study of China and the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (3), 910-921.

- Moore, R. J. (2009). Twitter Data Analysis: An Investor’s Perspective. TechCrunch Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://techcrunch.com/2009/10/05/twitter-data-analysis-an-investors-perspective-2/

- Jungah , L. & Amano, T. (Mar 21, 2013). Facebook Targeted in U.S. as Asian Chat App Line Invades. Blomberg News Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-03-21/face booktargeted-in-u-s-as-asian-chat-app-line-invades.html

- Hong, K. (Jun 3, 2013). Leaked Line document sheds light on one of its monetization models: corporate accounts. The Next Web Retrieved Dec. 26, 2013, from http://thenextweb.com/asia/2013/06/03/line-leaked-document-sheds-light-its-monetization-model-of-promoting-official-accounts-to-companies/

- Acar, A. & Ohniwa, M. (2023). Understanding Whys and How’s of Marketing on Group-chatting Applications. Paper presented at the 2013 ISIS Conference, Key West, FL.

- Sakamoto, K. (2013). An exploratory study about popular social media campaigns in Japan. Unpublished graduation thesis. Kobe City University of Foreign Studies, Tarumi, JP.